Ireland's Brigid: the Mythology of a Goddess, Deity and Saint

From the desk of the artist Alana Clohessy, in a small corner of Paris, on the Left Bank of the Seine.

Before we begin, I just want to remind you on Sunday, February 23rd at 6pm CET (Paris, France), I will be hosting an exclusive 90 minute, online writers workshop for paid subscribers of Tea with Alana. All paid subscribers will be emailed with information about the workshop. Come write with me and see what magic we create. If you would like to join, you can become a paid subscriber below for just €2 a week. This is suitable for writers of all levels, from beginners to seasoned pros and those experiencing writer’s block. This prompt based workshop will help foster new ideas and get words down on the page. There will also be time to share your writing with the group. Bring a cup of tea or your favourite hot beverage and we can have tea in person!

Saturday, 1st February, 2025. 6°C and Sunny.

Tea in my Cup: Twinings English Breakfast Tea with milk, no sugar.

Today is St. Brigid’s Day (Lá Fhéile Bríde in Irish), the first public holiday to be named after a woman in Ireland. As discussed in my letter last week (you can read it here if you missed it), Brigid is the second patron saint of Ireland after St. Patrick but she is much older than Christianity. Brigid belongs to the gods of the earth and walked the land of Ireland long before Christianity ever reached its shores. Brigid represents the light half of the year and is the goddess of spring, fertility and life. Artist’s are under her care.

When Christianity came to Ireland, the Church amalgamated Brigid into their teachings and feast day calendar, in a bid to keep the recent pagans, turned Catholics, satisfied. She was not a saint but a powerful deity to whom the Irish people worshipped. She was the goddess of sun and of fire. She was the protector of mothers and newborn children. She was the goddess of water and wells (many of Brigid’s wells can still be visited in Ireland and have remained places of pilgrimage for healing). She was the patron of brewers (beer was viewed as a nutritional and more sanitary alternative to water with most brewers in Ireland being women at the time) and the protector of bees. Sailours turned to her for protection during storms. These are just a few examples of her patronage.

Brigid was at the centre of life in Ireland and touched many aspects of our existence on a very personal level. Attempts to quell her influence and teachings over the years, by people who sought to belittle women’s voices and autonomy, along with suppressing the ancient Irish culture, prevailed for a while but the spirit of Brigid and what she represented, has remained within the Irish psyche.

Brigid, who she was and what she taught, is experiencing a revival in Ireland. A deep connection to the ancient land, women’s voices and the soul of nature. St. Brigid’s Day became a public holiday in Ireland, in 2023.

The folklore around Brigid is varied but all say she is daughter of the Dagda, a king of the Tuatha dé Danann (People of the Goddess Danu). The Tuatha dé Danann were an ancient supernatural race that came to Ireland on dark clouds and landed on the mountains in Connaught (a province on the West coast of Ireland).

The Tuatha dé Danann were defeated by the Milesians (thought to be the first Celts). While the Tuatha dé Danann were allowed to stay in Ireland they were forced underground where they became known as the Sidhe (fairies). Old Irish scripts describe Brigid’s father, the Dagda, as

“a beautiful god of the heathens, for the Tuatha dé Danann worshipped him: for he was an earth god to them because of the greatness of his magical powers”.

He could control life and death, the weather and crops, as well as time and the seasons.

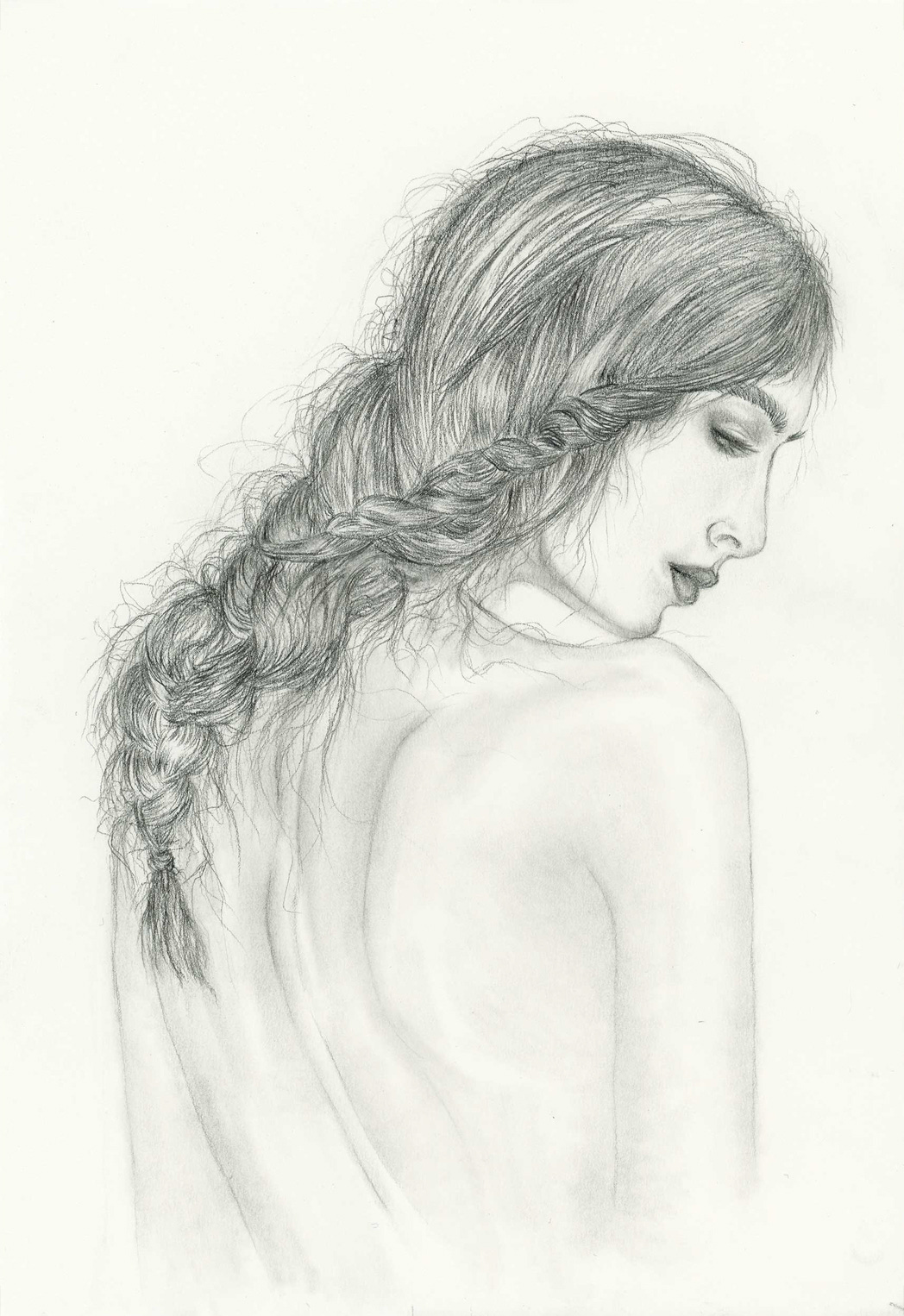

Brigid, the Dagda’s daughter, was born with the sunrise, and the goddess whom poets adored.

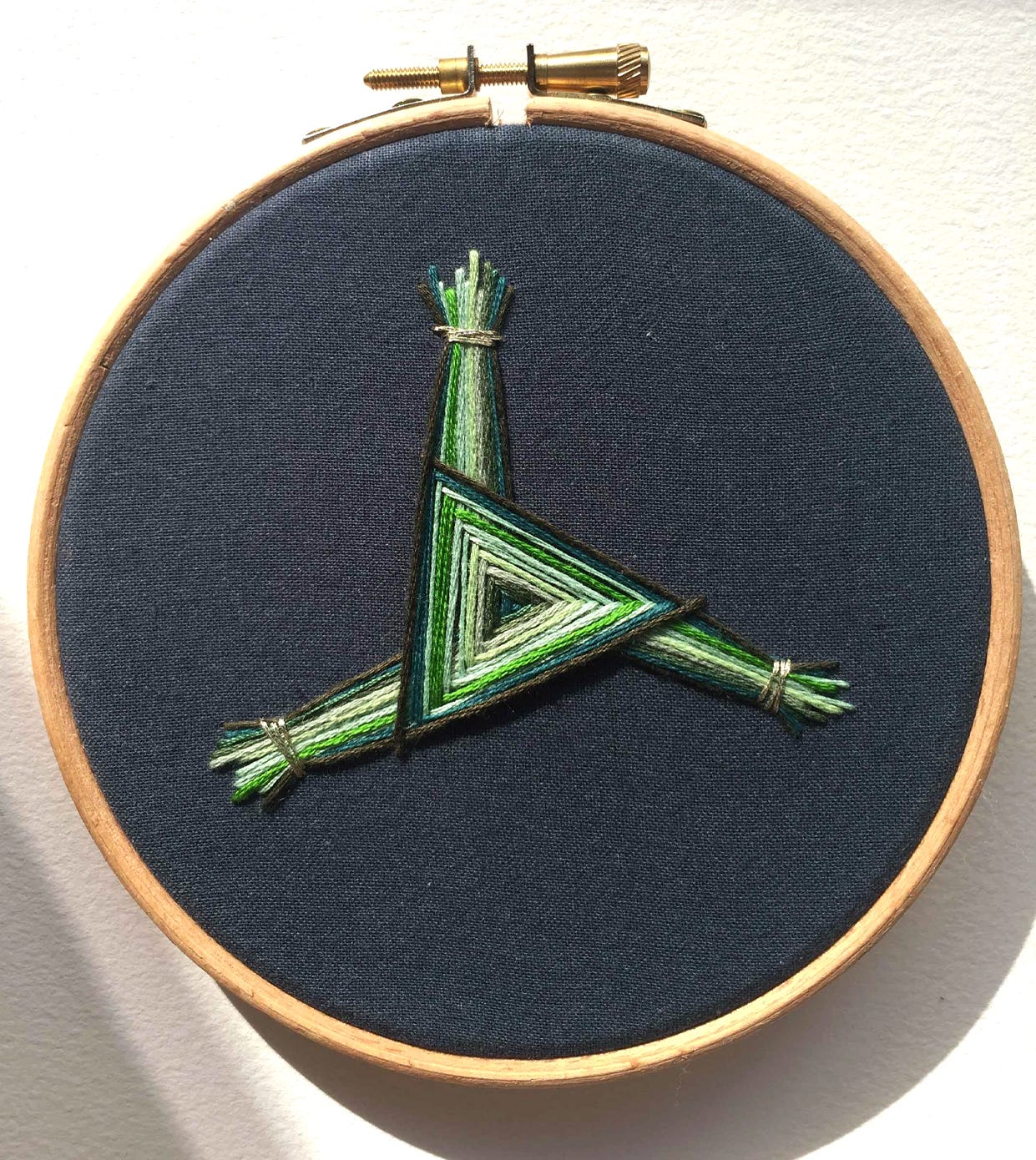

The Brigid’s cross is one of the most enduring symbols of Brigid today. Woven from freshly picked rushes on the 31st of January each year, Brigid’s crosses have been made for thousands of years in Ireland, long before Christianity. On Imbolc (February 1st), the woven crosses were hung above doors and mantels in the home and above the doors of animal sheds, to honour Brigid and to protect against fire, storm, lightening, illness and epidemic.

Imbolc is one of the four fire festivals in Ireland. It marks the beginning of Spring and the midpoint of winter. It is celebrated as the end of darker days, heralding rebirth, reawakening and new beginnings. Imbolc was the ancient festival of Brigid before it was renamed as St. Brigid’s Day by the Church. While Ireland follows the Gregorian calendar (enforced in 1752 by the British Empire as Ireland was still one of its colonies), Ireland has retained ancient Celtic festivals within it and recognises Spring as the first day of February. Met Éireann (Ireland’s National Meteorological Service) will use the meteorological calendar but if you ask any Irish person when Spring starts, most will say February 1st.

There are many variations of Brigid Crosses including two armed, three armed and four armed crosses. Straw dolls were also made for her in certain parts of Ireland. The prevailing cross today is the four armed cross of Brigid, thought to have been encouraged due to its similarity to the Christian symbol of the cross. This however remains speculation.

To this day, Brigid’s crosses are hung in homes around Ireland. I was taught to weave these crosses in school as a child. The last cross that I made in school, so long ago, still hangs in my parents’ house above the door. When I first emigrated to Canada in 2012, a friend sent me a Brigid’s Cross for protection and to celebrate my new home. She was Scottish and lived in Ireland. She did not know the significance of the cross when she sent it to me. She bought it for me at the artisanal Galway Market in Ireland (I used to live in Galway before I emigrated). She asked the stall owner and artist, if he could recommend something for a new home and he gave her a cloth covered Brigid’s cross. I couldn’t believe it when I opened the package in Vancouver. It was an auspicious sign. Brigid had always been part of my childhood in Ireland and now she had followed me across the ocean. It hung on my very modern, apartment door, much to the confusion of Canadian visitors.

Along with the shamrock and harp, Brigid’s cross has become a symbol of Ireland. It was formerly the symbol of the Department of Health and the station identifier for Raidió Teilifís Éireann (Radio and Television Ireland - the state broadcaster, one of the oldest, continuous public broadcasters in the world) until the 1990’s. It remains a logo for An Bord Altranais, the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland. When I moved to Paris in 2020, I could not gather fresh rushes on Imbolc Eve. In lieu of rushes, I wove the cross with thread.

Last night, I celebrated Imbolc at the Irish Culture Centre in Paris (Centre Culturel Irlandais in French). Those of us living here, call it “CCI” for short. The CCI is Ireland’s cultural flagship in Europe and located in Paris, at 5 rue des Irlandais (Irish Street) named by Napoleon in 1807 by a prefectoral decree. I have spent many a night there, talking to other artists, listening to song and watching plays. Sitting under the cool trees in the courtyard with friends as the sizzling sun of summer sets and bracing the cold winds during winter festivities. I will speak more about the Irish Culture Centre in Paris in another letter as it holds a fascinating story and is an integral part of Ireland’s history in France.

In old Celtic tradition, the day began and ended at sunset. Imbolc begins at sundown on January 31st and ends as the sun sets on February 1st. The night began with Irish harpist Brenna Byrne, playing and singing in the old chapel of the Culture Centre which still holds mass every Sunday at 11.30am and where intimate concerts are played. The acoustics haunting. Then there was a talk by the Irish artist Tom Climent whose paintings were exhibited in the gallery. As the sun went down and the light left the sky, sculptures by artist in residence Tom Meskell, dotted throughout the courtyard, began to glow. Female and child lantern figures, stood hauntingly in the Imbolc night under the dark, turbulent rainclouds. Pictures drawn by infants in school, lined the walls of the courtyard. A small food truck sold crepes with chocolate sauce. Wine was poured free of charge.

There is so much mythology around Brigid that I could not possibly cover it all in one letter but there is one more aspect that I will share with you and it is one of my favourites. It is the story about St. Brigid’s Fire Temple and the Daughters of the Flame.

Long before Christianity came to Ireland, a group of priestesses tended a perpetual sacred flame on the hill of Cill Dara (Church of the Oak) now known as Kildare in Ireland. Using the flame, the priestesses would invoke the goddess Brigid to protect their herds and provide a fruitful harvest. They were the Daughters of the Flame.

In the 6th century and with the dawn of Christianity, a nun later to be known as St. Brigid, established the first monastery in Ireland on that same hilltop. It ultimately became known as the Fire Temple of St. Brigid and the custom of keeping the sacred fire alight continued.

The Fire Temple was surrounded by a circular hedge made of stakes and brushwood which no male could cross without being killed, crippled or cursed to go insane by divine intervention. Twenty nuns, including the nun Brigid, would tend the perpetual fire. Each night, one nun would each take it in turn, to guard the flame alone.

After the death of Brigid, they did not replace her. The nuns would tend the fire for nineteen consecutive nights and on the twentieth night they would say, “It is Brigid’s turn”. Wood was placed by the fire and they would leave. On their return in the morning, the fire would be lighting and the wood gone. Every twentieth night, the spirit of Brigid protected the fire, unseen, throughout the hours of darkness.

The fire continuously burned until the 16th century when the original flame of Brigid was extinguished by King Henry VIII and the Norman Church hierarchy in an attempt to end the trappings of the Celtic Church deemed overtly pagan. In 1993, the flame was relit by Sr Teresa Cullen, the congregational leader of the Brigidine Sisters - a small group of Catholic nuns who follow the order of St. Brigid, in Kildare, Ireland.

Today the flame is still alight and guarded by the Brigidine nuns, as it was in Kildare many centuries ago by the Daughters of the Flame. You can visit Brigid’s Flame in Kildare, at Solas Bhridhe (Brigid’s Light), a Christian spirituality centre run by the nuns in Ireland. They welcome people of all faiths and of none.

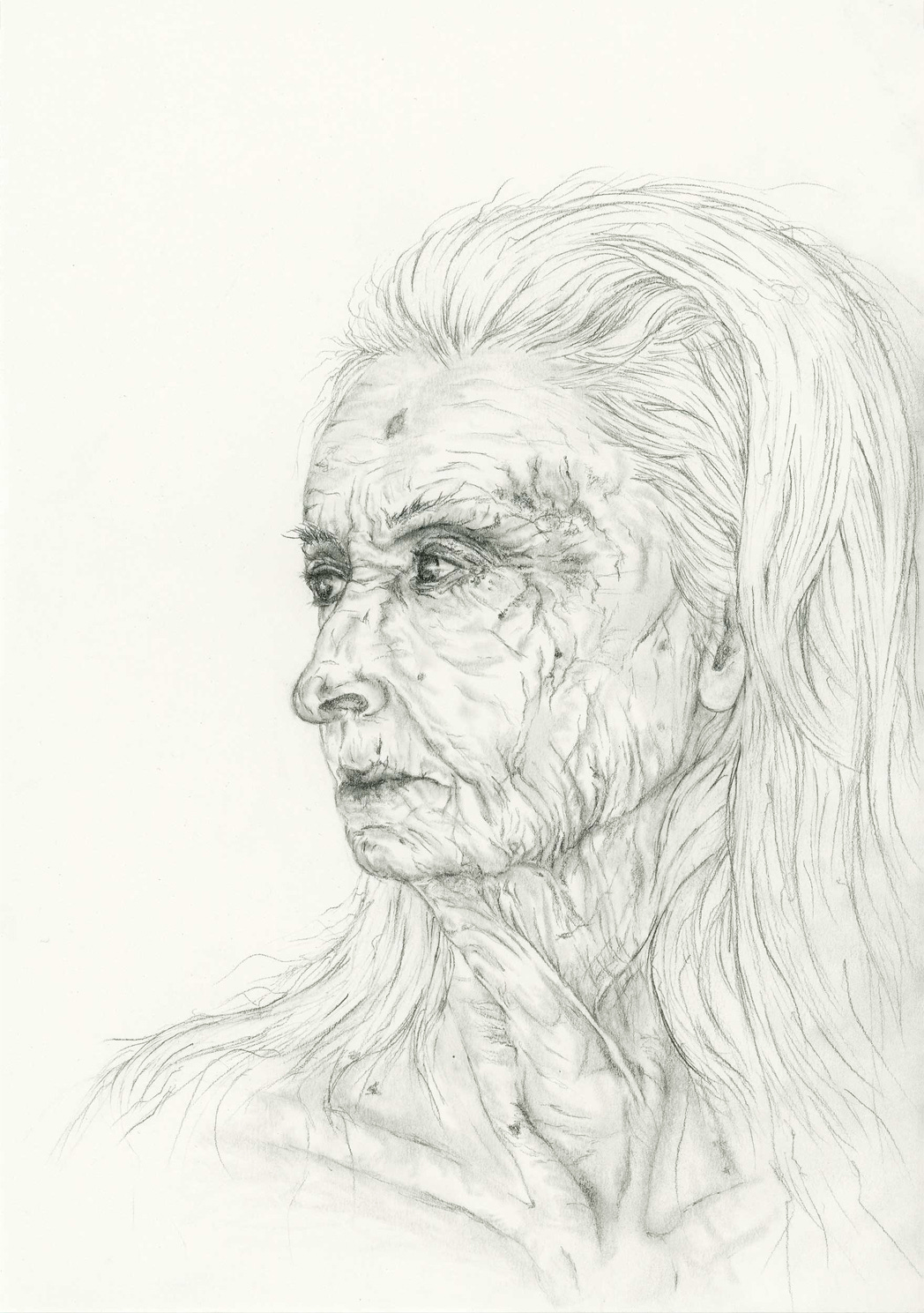

Following on from my letter last week and for those who missed it, we spoke about the Cailleach, the Divine Hag of Ireland. While Brigid governs the light half of the year, the Cailleach governs the dark half and brings with her winter, thunder and storms. It is said if the weather is fine and sunny on Brigid’s day (from sunset last night 31st January to sunset tonight February 1st) the Cailleach is collecting her firewood to create more blazing fires in her hearth as she is extending winter with its cold wind and turbulent storms. If the day is foul, the Cailleach is asleep and winter is almost over, the promise of sunny spring days ahead. As mentioned last week, this is still celebrated in the United States as Groundhog Day but the Cailleach, unfortunately, has been removed.

It absolutely lashed rain last night but today it was clear and the sun was shining. The jury is out on whether the Cailleach was collecting her firewood. Only the coming weeks will tell.

Au revoir - until we meet again,

Alana x